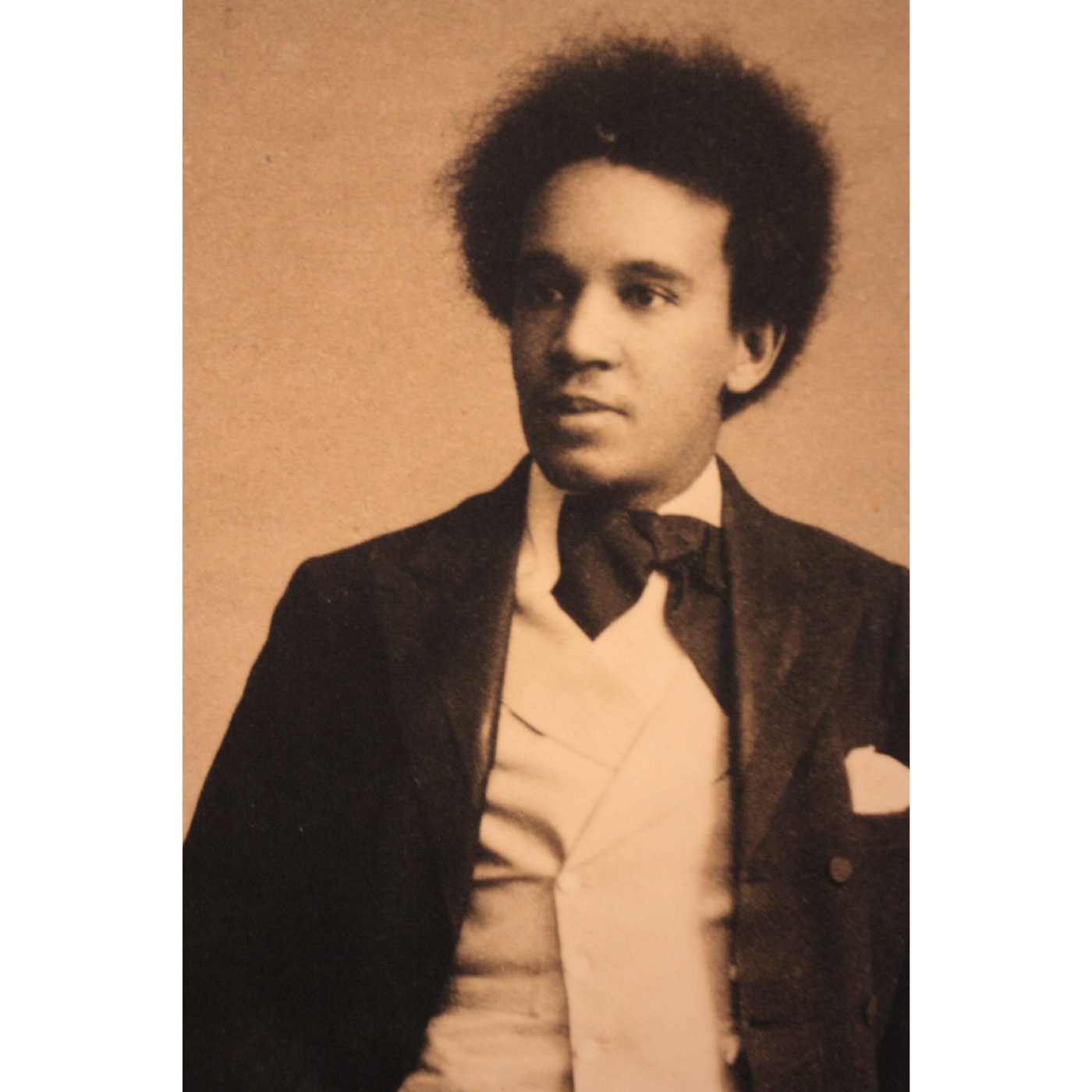

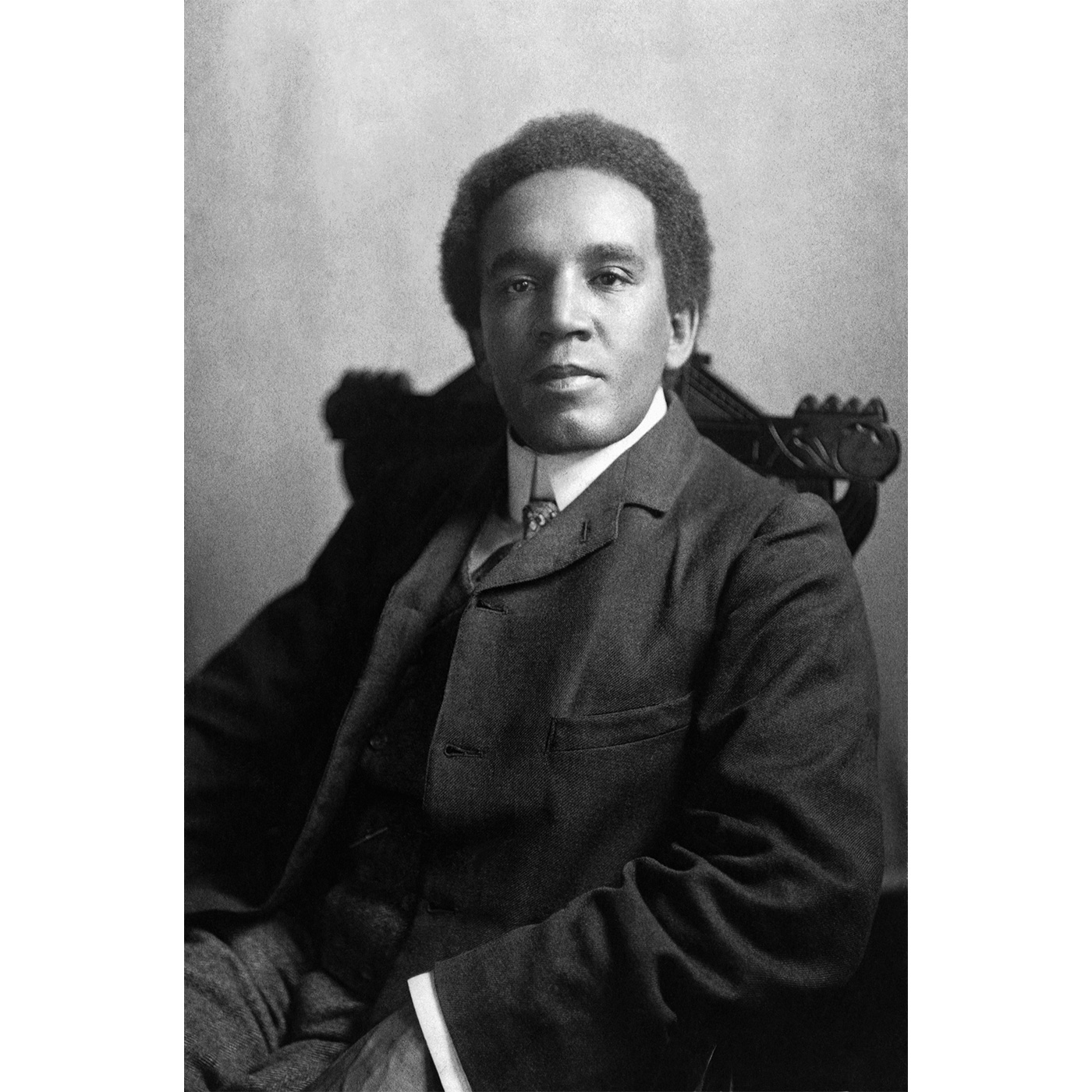

This week we are joined by guest writer Grace Healy, who is a Peckham-based piano teacher and plays keys in Croydon band Bugeye. Grace, who is campaigning for the inclusion of black composers on the ABRSM syllabus, shares the history of Croydon-raised black composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912).

Only those with a keen interest in the history of classical music will know how successful the composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor really was. Born in Holborn and raised in Croydon, Samuel – or ‘coaley’ as he was cruelly nicknamed at school – was world famous by the time he was twenty-five and hailed a genius by his contemporaries.

His father, Dr Daniel Taylor, was born in Sierra Leone and studied at King’s College, London. When Samuel was a small child his father returned to his home country after the failure of his medical practice in London, never to meet his son. His mother, Alice Hare Martin, moved in with her father and later married storage railwayman George Evans.

Samuel demonstrated musical promise early on. As a young boy he was given a violin by his grandfather who taught him how to play. After his voice broke, he joined the choir of St Mary Magdalene’s Church in Addiscombe led by Colonel Herbert Walters. In 1890, at just fifteen years old, he was awarded a scholarship (arranged by Walters) to the prestigious Royal College of Music as a violin student. He was one of the first black musicians to be accepted at the college, studying alongside now revered composers Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams. Although he initially enrolled as a violin student, Samuel showed an aptitude for composition and went on to study under the supervision of composer and conductor Charles Villiers Stanford. His reports from the RCM reveal that he excelled in his studies, and was even described as ‘one of my cleverest pupils’ by his piano tutor.

It was during his time at college that he met student pianist and future wife Jessie Walmisley. Initially, Jessie’s parents objected to the marriage due to Samuel’s mixed parentage and did everything in their power to prevent it. Eventually, the day before the wedding, the Walmisley’s relented and invited Samuel to their home where they finally shook his hand in acceptance. The couple married in 1899 in his parish church in Selhurst to witnesses Colonel Herbert Walters and Walter Milbanke Walmisley (the bride’s father). The couple had two children: son Hiawatha and daughter Gwendolyn. Gwendolyn later took the name Avril and became a conductor-composer in her own right, serving as the first female conductor of the H.M.S Royal Marines.

It was in 1898, a year before his marriage, that he became a household name after the premiere of his cantata Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast (which was later developed into a trilogy) was held at the RCM. He was an overnight sensation and the work was hailed a masterpiece by the press. Unfortunately, Samuel had already sold the copyright to publishing firm Novello for a mere fifteen guineas: thousands of copies of the score were sold and he didn’t see a penny. By 1904 Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, based on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem on the adventures of Native American hero Hiawatha, had been performed two-hundred times in England. By the time he left college Samuel was a published and widely performed composer. Despite his success he still wasn’t earning enough money to keep him afloat and had to find teaching and conducting work to subsidise his income. Between 1901 and 1904 he taught at the Croydon Conservatoire, Trinity College of Music, and the Crystal Palace School of Art and Composition.

He was also successful in America at a time when African Americans were suffering from the worst repression they had experienced since the Civil War. Samuel, however, was welcomed as a celebrity: he dined at the White House, was praised by President Theodore Roosevelt and black educationalist Booker T. Washington, and it was in America that he became the first black man to conduct a white orchestra. In 1901, the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society for black Singers formed in Washington D.C. This moment was a turning point in American history: the image of the serious black musician began to take shape. Samuel proved that musical genius was not inherent to the white man and gave hope to black Americans.

More recently, scholars have commented on Samuel’s role in the formation of African American networks in London. In 1900, at twenty-five years old, he was a delegate at the first Pan-African Conference in London. Historians have referred to this meeting as ‘one of the starting points for the Afrocentrism that constituted an important strand of the American Civil Rights Movement sixty years later’. Among the attendees were many notable civil rights leaders, politicians and educators.

In 1912, at just thirty-seven years old, Samuel collapsed at West Croydon Station and later died of pneumonia at his home in Croydon. The press published warm tributes, a huge wreath was made by the ‘sons and daughters of West Africa residents in London’ in the shape of South Africa, and his funeral procession through Croydon was three and a half miles long.

A statue of Samuel can be found on Charles Street (just behind Exchange Square) where he’s been commemorated alongside other famous Croydonians, Dame Peggy Ashcroft and Ronnie Corbett (as voted by the public back in 2013). There is also a blue plaque on his former South Norwood home on Dagnall Park, which was erected in 1975. Astoundingly he was the first black recipient of English Heritage’s blue plaque scheme celebrating notable Londoners.

It is absolutely extraordinary that a man of such musical genius, who enjoyed worldwide fame at the beginning of the twentieth century, has been written out of our wider musical history.

To ensure the representation of black composers such as Samuel Coleridge-Taylor on music exam syllabi, please sign my petition here.

Posted by guest writer Grace Healy.

Portraits of the composer from Wikimedia Commons, Charles Street statue photos by the Croydonist.

I am delighted you have included this article. Back in 2012 there was a year long Festival to commemorate the composer’s death conceived by Jonathan Butcher of Surrey opera with the support of the Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Network, which I co-ordinate. Joint founder members of the Network were Jeffrey Green, the composer’s biographer and Fred Scott, Croydon pianist teacher and composer, Using my publishing imprint History & Social Action Publications a pamphlet by Jeff was published. This was re-printed last year – details on the Network’s website at https://sites.google.com/site/samuelcoleridgetaylornetwork In work I have carried out with Durham University on slavery and abolitionm, the black presence and the important role of University music students and staff in promoting the composer, I have submitted a project proposal on the University’s links with Sierra Leone, where the composer’s father came from, and about George (Coleridge-) Taylor a student from Sierra Leone, who was a descendent of the composer’s father. Tayo Aluko, whose one man show Call Mr Robeson has been oerformed in Croydon is developing a one way show about George and his interest in the composer. It was supposed to have been tested in the Croydon Theatre Festival which had to be abandoned because of the COVID crisis.

This is great to hear Sean. Thank you for sharing.

I live in St Leonards road and there is a blue plaque on the house opposite mine. It was placed on number 6 a few years ago by the coleridge taylor society. We had an unveiling of the plaque ceremony and some of his family came from Sierra Leone . The plaque says its where he died

There is also a blue plaque on his former home in St. Leonard’s Road in Waddon, placed there in 2012 on the 100th anniversary of his death.

Thanks for letting us know Austen. We’ll look out for it when we’re next in Waddon.

The plaque was put up as one of the final events in the year long Festival remembering the death of the composer, organised by Jonathan Butcher of Surrey Opera. 2012 I arranged for Nubian Jak Community Trust to do the project. The Trust puts up plaques to black people mainly in London, and was also responsible for the African and Caribbean War Memorial in Windrush Square in Brixton. The pamphlet I published under my imprint History & Social Action Publications by Jeffrey Green sold out. I reprinted it last year, so copies are available – see the Network website.

Famous son of Croydon & talented trailblazer. Thank you for all this great info.